Chicago's Camp Douglas 1861 – 1865

Brief History

Chicago played a significant, non-battlefield role in The War of Secession (The American Civil War) 1861 – 1865. Camp Douglas was at the center of that role.

During the four years Camp Douglas was active it served as a reception and training center for Union soldiers, a camp for paroled Union soldiers until their exchange, and a prison for captured Confederate soldiers.

In 1861 the Confederate Army captured Fort Sumter in Charleston South Carolina. On April 15, 1861 President Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers for the Union army.

On April 16, 1861 Illinois Governor Richard Yates issued a call for 6,000 Illinois volunteers. Within several weeks the response exceeded expectations and enough volunteers came forward to form 38 companies.

The state of Illinois was expected to not only raise and organize troops, but the state was required to quarter, subsist, equip and train them.

Enlistees in Chicago were housed at various locations around the City in at least 7 "temporary camps" including one known as Camp Douglas which was the future site of the formally established Camp Douglas.

The decision to formally locate Camp Douglas on Chicago's near south side was made in early 1861 and construction occurred in September and October of 1861.

Camp Douglas consisted of 60 to 70 acres of land donated by Chicago land owners including Henry Graves who donated 30 acres. Camp Douglas was named for Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas who owned land in close proximity to the Camp but his land was not used for the main functions of the Camp except for a small parcel used for the smallpox hospital.

Beginning in September 1861 Camp Douglas and its satellite camps (approximately 10 in number including Camp Hancock- see letter on this web site) served as reception and training centers for Union soldiers. The majority of Union soldiers were mustered in by February 1862 with smaller units being organized through December 1864.

Camp Douglas became a prisoner of war camp in February 1862 and received Confederate soldiers after Union victories including Fort Donelson in Tennessee as well as Shiloh and Island 10. The prison population grew to over 12,000 by December 1864 after the abandonment of prisoner exchanges as noted below.

In July of 1862 the Dix-Hill Cartel was signed by representative generals of the Union and Confederacy and included a series of Articles which dealt with the parole and exchange of all prisoners of war. By September of 1862 approximately 7,800 Confederate prisoners were exchanged and were sent to Vicksburg Mississippi or City Point Virginia. At this date the Camp was nearly empty.

In September 1862 12,500 Union soldiers were captured at Harpers Ferry Virginia and were released on parole under the provisions of the Dix-Hill Cartel and were sent to camps in the Northern states including Camp Douglas. The Union parolees were of the opinion that they would be released by the commanding officers of the northern camps but instead they remained in these camps until they could be exchanged.

Early in their paroled status the Union soldiers realized that under the provisions of the Dix-Hill Cartel they were to be confined to camp, required to drill, perform guard duty and Indian fighting and were not to perform any duty usually performed by soldiers until exchanged. This led to insubordination and turmoil at Camp Douglas.

By December 1862 Union parolees at Camp Douglas had been exchanged and captured Confederate soldiers began arriving at Camp Douglas.

In 1863 President Lincoln drafted a General Order and by mid-1863 prisoner exchanges no longer took place at any Northern prison. This resulted in a significant growth of the prisoner population in Camp Douglas.

Over the remaining months of the war conditions at Camp Douglas deteriorated resulting in the deaths of 6,000 incarcerated prisoners. Factors contributing to these deaths include growth of the prison population resulting from the termination of prisoner exchanges, Chicago's harsh weather to which southern Confederate soldiers were unaccustomed, significant disease from lack of water, sewer drainage, and lack of planning for long term incarceration.

Chicago's Camp Douglas 1861 – 1865

The Mail History

With Camp Douglas large population over its four year history many packages and letters passed to and from the Camp through the Chicago Post Office.

The dates of each type of use of Camp Douglas, whether training, parole, or prison are known in general with some discrepancies depending on the information source. Examination of the postmark date of any envelope or letter often helps identify the writer as a trainee, a paroled soldier, or a Confederate prisoner.

Letters sent by Union soldiers in training at Camp Douglas usually bore no special markings provided the required postage was affixed.

Letters sent by Union soldiers while in the parole camps of the North sometimes bore a hand written marking indicating "parole". In one instance a letter written from Camp Parole in Annapolis Maryland had a sticker affixed to the front of the envelope. Camp Douglas was one of the federal parole prisoner camps in the Northern states.

Generally, prior to 1863, most envelopes sent from federal prisons in the North bore a hand manuscript marking indicating examined or approved. However many such mailings had no such markings?

The majority of envelopes and letters in collectors' hands and sent from Camp Douglas were written by Confederate prisoners and were postmarked Chicago.

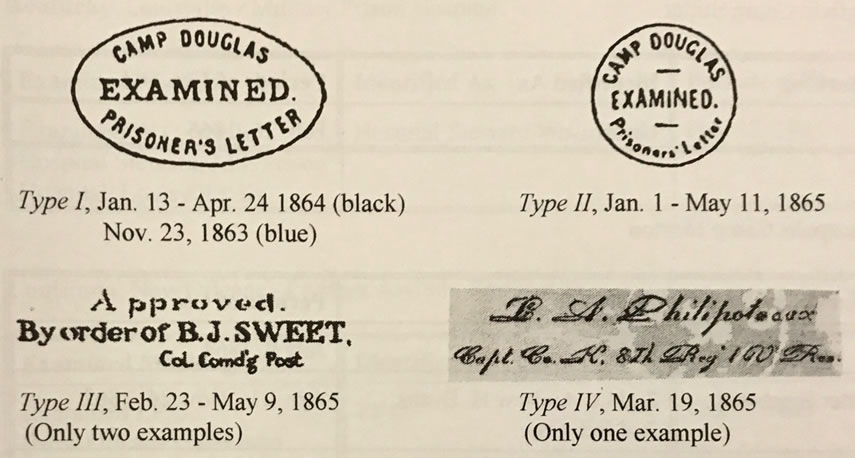

Letters written by Camp Douglas prisoners during 1863 and in later years were often hand stamped (as opposed to hand written) "EXAMINED" on the envelope indicating the contents was reviewed. In addition a few rare examples exist where the letter was also stamped with a separate "Approved" handstamp. Samples of envelopes appear on this web site. All four known examined or approved handstamps from Camp Douglas appear below.

Source: Prisoner Mail from the American Civil War by Galen D. Harrison published in 1997 by Thompson-Shore Inc.

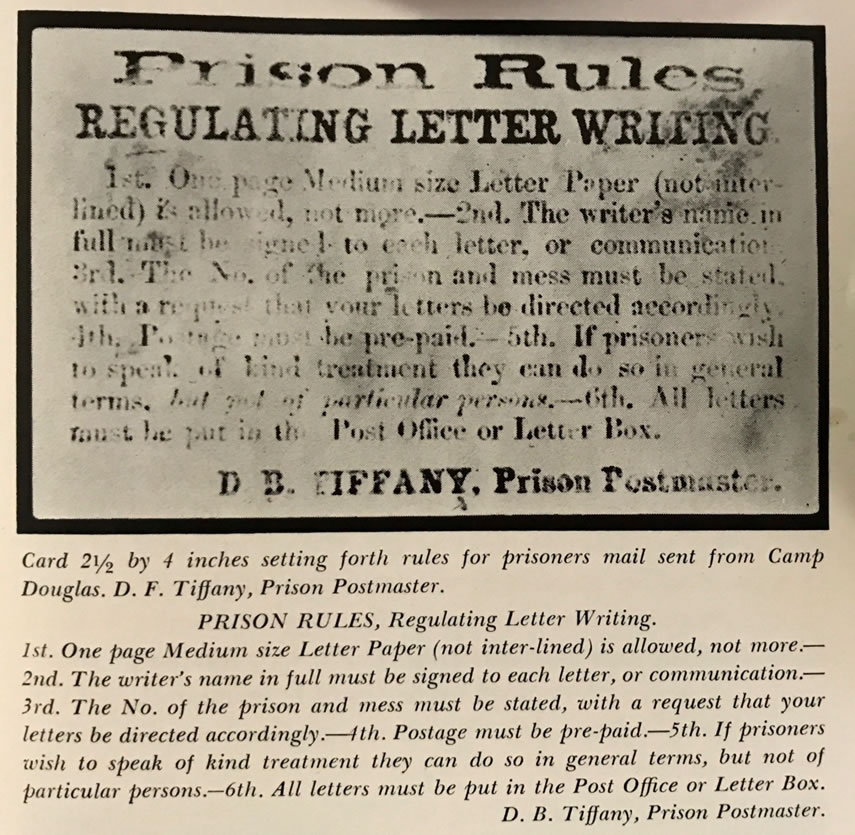

Letters mailed from Camp Douglas had specific requirements as shown by following which appeared in Civil War Prisons and Their Covers by Earl Antrim published in 1961 by the Collectors Club of New York. (The image quality of this rare document is as it appears in the book.)

Postage requirements varied depending on the destination. Camp Douglas mail sent to Northern states had one postage requirement compared to through-the-lines destinations which were sent to Southern states. The latter were often marked "Flag of Truce" letters.

A discussion of the postage requirements can be found in the Antrim book referenced above. Additional sources include Prisoner Mail from the American Civil War by Galen D. Harrison published in 1997 by Thompson-Shore Inc., Camp Douglas & its Prisoner of War Letters by Richard McP. Cabeen published in 1951 appearing in the Seventeenth American Philatelic Congress of Original Papers on Philatelic Themes.